– post by Tristan Harrenstein, Florida Public Archaeology Network

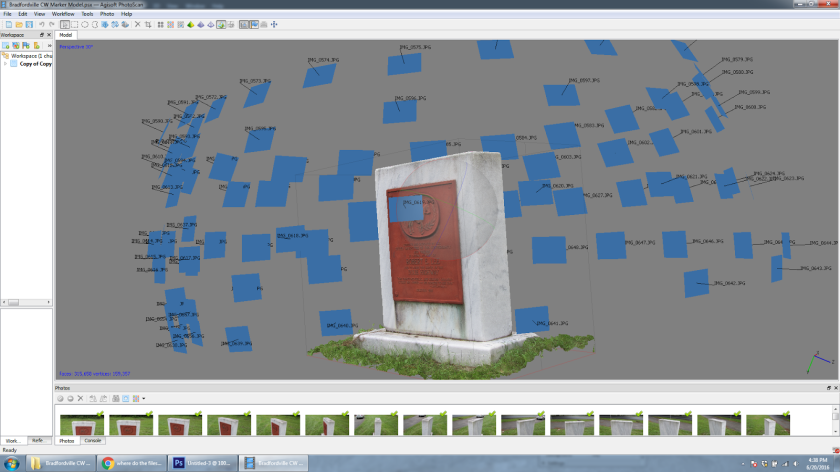

In the last few years, archaeologists have been getting excited by the potential for recent advances in something called photogrammetry. This technology takes a collection of photographs of an object, plugs them into a program (Agisoft PhotoScan in this case), and builds a digital 3D model.

This is exciting! Photogrammetry is already useful for research and education, but it is also changing the way we record archaeological sites. Dr. Kotaro Yamafune (Research Associate in Nautical Archaeology at Texas A&M University) has an impressive body of work using this technology to record underwater shipwrecks. After five days of photographing, he was able to generate highly accurate and easily manipulated maps that would normally take years and many divers. The use of photogrammetry saved money and people hours, without sacrificing accuracy or data.

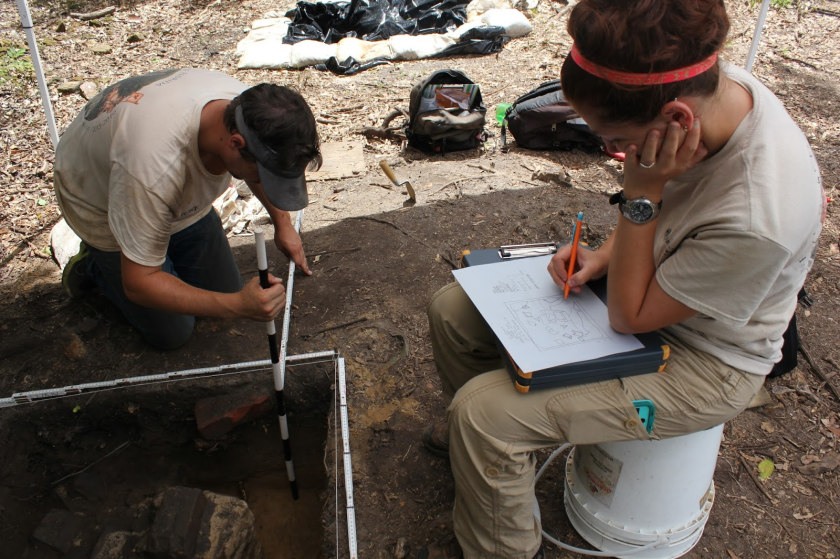

Which brings us to the purpose for this blog post. Since there has been so much success modeling underwater archaeological sites, what potential does photogrammetry have for sites on land? Might this technology someday replace hand drawn maps? To test this, Barbara Clark and I visited Florida State University’s archaeological field school this summer and modeled one of their excavated units.

One limitation of photogrammetry software is that it needs identifiable features so that it can figure out where each picture was taken in relation to the others. I was concerned that the unit walls would look too much alike for the program to align the pictures properly. As a result, we made two models of the same unit. The first set of photos were of the plain unit walls while the second set included some photo board symbols pushed into the sides to provide points of reference for the program.

The Results

To be clear, this experiment was not supposed to be definitive. The goal was to get some idea of how much potential there currently is for photogrammetry as a tool for recording terrestrial archaeological excavations and to better understand what equipment we would need. That being said, these models turned out far better than I had expected, with very little difference in quality between the two tests.

See an example of the terrestrial photogrammetry we did on one excavation unit at the FSU Anthropology’s 2016 Archaeological Field School HERE!

*Please note, these examples are using just 500k faces each. A much higher resolution of 25 million faces is possible, but not many computers can currently handle this.

As far as the equipment goes, we need better photographing methods. Even with the monopod, taking pictures of a unit this deep was difficult and uncomfortable. I spent a lot of time with my head in the unit, or standing at awkward angles inside the unit, trying to hold still for the camera while yellow flies gleefully seized upon the opportunity to grab a bite.

On the upside, the solution to this is relatively simple. All we would need is a pvc pole, a camera mount for bicycle handlebars, and a remote for our camera. This would take a few test shots to make sure the angle was correct, then the rest would be faster and much more comfortable. Throw in a white tent to help diffuse the light evenly and we should be in good shape.

But is this worth pursuing further? We certainly do not have the same limitations on land that our underwater peers do, and photogrammetry cannot replace hand-drawn profiles of unit walls any more than pictures can (due to a tendency to distort colors). Does this mean that photogrammetry has no current value for terrestrial archaeology?

Absolutely not. There are a lot of ways this technology could be invaluable right now. Do you have an artifact that you cannot take back to the lab with you? A few minutes of photographing means you can examine it later at your leisure. This also has excellent applications for complex features that do not just rely upon soil changes, such as brick structures. Photogrammetry models provide a sense of depth that even the most diligent hand-drawn maps or pictures cannot capture very well.

Mapping a feature like this one on 2D graph paper is very challenging and time consuming. Photogrammetry is already an improvement for a situation like this.

In a nutshell, photogrammetry currently has some excellent, if situational, uses in terrestrial archaeology. Perhaps this will revolutionize the way we record sites, or perhaps it will just remain a very specific tool for a specific job. However, technology is advancing quickly and I would not be surprised if photogrammetry, scanning, or just tablets make hand-drawn profiles obsolete someday. We will need further testing to fully understand the potential of photogrammetry, but now is the time to begin.

Tristan Harrenstein is trained as an archaeologist and has a passion for outreach and education. This is fortunate as he is also an employee of the Florida Public Archaeology Network, an organization dedicated to promoting the preservation and appreciation of our archaeological resources. He shares a blog space with his boss (Barbara Clark) and you can read more blog posts on other archaeology related subjects that tickle our fancy here.